Above, Illustration of Edwin Booth as Richard, in an engraving published in Booth's own acting edition of the play in 1872.

Edwin Booth first played the Academy of Music in the role of Richard III on August 24th 1863 . The production was produced by his business partner, his friend from childhood, John Sleeper Clarke, who was also married to his sister Asia.

The evening went well. "The house was radiant with the beauty and intelligence of the city to witness Mr. Booth as 'Richard III'," reported the Philadelphia Inquirer. "It is needless to say that he sustained his reputation, since this piece is one in which he is always eminently successful."

Below, Booth's childhood friend and business partner, the comedian John Sleeper Clarke (1833-1899) and his sister Asia Booth Clarke (1835-1888). Early in their marriage they lived in Philadelphia, though they later became estranged. Sleeper Clarke was arrested and imprisoned in April of 1865, as part of the general round-up of associates of John Wilkes Booth in the panic following Lincoln's assassination. He never got over the experience, and blamed Asia and the Booth family for the indignities he suffered. He went on to have a successful career however, and after buying out his brother-in-law he retained his ownership of the Walnut Street Theatre. Indeed the family only finally sold it in 1919.

Above, a bill for Booth's performance of Richard III at the Academy, from the collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Twelve years later, on October 22nd, 1878, Edwin Booth again performed Richard III in Philadelphia - but at the Broad Street Theatre, opposite to the Academy.

The Broad Street Theatre, an elaborate and showy Moorish palace which had been built by the Kiralfy Brothers for the occasion of the 1876 Centennial, was directly across from the Academy of Music.

Below, the tunic Edwin Booth wore as Richard - which you can see him wearing in the print at the very top of this post. It is now in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Richard III was not nearly as important to Edwin Booth's career as his Hamlet and his Iago were to be. But as part of the standard repertoire of roles that any leading male classical actor of his day was supposed to master, it is significant that John A. Arneaux chose this one as the role to make his Philadelphia debut. Also significantly, like Booth, Arneaux did not surround his performance with after-pieces or variety acts. In the post-Civil War era, Shakespeare's plays were now expected to be performed as the sole entertainment of the evening. Their appeal was no longer to the broadest audience possible, but to an increasingly educated and well-heeled section of the public. This formula would work well for Booth, who died a very wealthy man. But as we shall see, it was a formula that would lead Arneaux to only frustration - and eventual obscurity.

(For Bibliography and references, see our blog post entitled "The Happy Possessor of a Noble Ambition")

Heritage House - Images for Episode 102

Above: John Allen leads a movement class in the basement of Heritage House.When the John Allen and the Freedom Theatre first arrived at Heritage House in the fall of 1970, according to Inquirer reporter Bill Thompson,"the basement was a wreck - sixt…

Killer Joe Canuso - Images for Episode 101

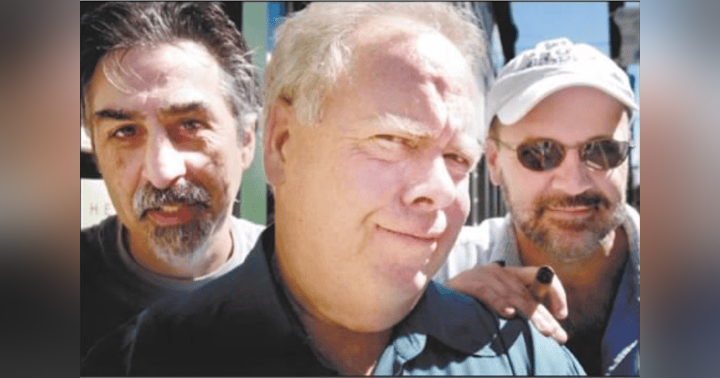

Header image, above: Joe Canuso, Tom McCarthy, and Bruce Graham pose for a promotional article about The Philly Fan in the Inquirer in 2004 (photo by Vicki Valerio).Below, a feature article about Canuso that was printed in the Inquirer on April…