"George Frederick Cooke as Richard III", by Thomas Sully (1811). Collection of the Philadelphia Academy of the Fine Arts.

Visiting this painting again, it strikes me more than ever how the viewer is actually placed as if they were in the action of the play. It's as if we are Lady Anne, and have just passed the column in the right foreground. Behind it we discover Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who has been lurking there, waiting for us. His vulpine smile both repels and attracts us. The implied motion is an astonishing, almost cinematic, property of the image.

This portrait has been on the stage, too! In October of 1812, after Cooke died, the Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia held a special ceremony to honor his passing. The portrait was exhibited for the first time in public, while a 'monody' - solemn poem of remembrance to Cooke - was read aloud.

Below, another portrait of Cooke made by Sully in the Spring of 1811, now apparently in a private collection. (A third portrait that Sully made of Cooke is in the collection of the Walter Hampden-Booth Theatre Library in New York, but is not currently available on public databases.)

Below are two portraits of George Frederick Cooke during the height of his fame in London.

Left, Cooke as Richard III in a portrait by an unknown English painter. Note that this Richard has a different costume than in the Sully portrait done in Philadelphia in 1811 - for instance, here he wears a hat, not a helmet, and the feathers are white, not black. Cooke famously complained that he had left all his usual costumes in England, because Thomas Cooper had bundled him off to America so quickly. Presumably Cooke was able to get some new costumes made for him in New York once he arrived. (The painting is in the collection of the Theatre Royal in Bath, England)

Right, Cooke as Iago from Othello, in a print made from another painting, in 1801. (Collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London)

There are many images of Cooke to choose from. He was one of the first real celebrities of the British stage in the 19th Century, and popular publications which wrote about the dramatic world were beginning to create a demand for prints of famous actors. Below are three popular prints that were made by David Edwin after other paintings of George Frederick Cooke, in the roles of Sir Pertinax MacSycophant, King Lear, and Sir Archy McSarcasm. These prints were also widely distributed in America, and copies were pasted into the book in the Penn Library, the one which contains all the carefully collected and pasted newspaper columns that Charles Durang wrote for a Philadelphia newspaper in the mid-19th Century. This book is now available online, and is usually referred to as Durang's History of the Philadelphia Stage, Between the Years 1749 and 1855 (See the Bibliography, below).

The roles of MacSycophant and McSarcasm were satirical comic roles, both written and performed by the famous Irish-born actor Charles Macklin (1690-1797). These were both parts which required a perfect Scots accent to perform. Cooke had spent his youth at Berwick-on-Tweed in the far north of England, quite near the Scottish border, so he was very familiar with the dialect - in fact, according to people who had seen both men perform them, it was said that Cooke's accent was actually much better than Macklin's! George Frederick Cooke had huge success in both these parts during his career, and the audiences for them always rivaled those of this tragic roles. Since Cooke's death, neither play has been much performed.

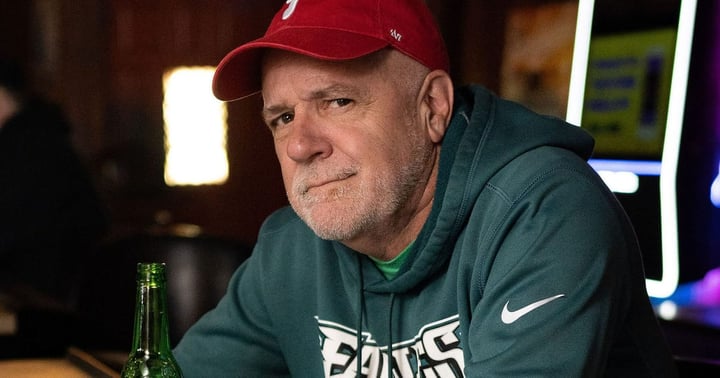

Below: Thomas Abthorpe Cooper (1776-1849), in an 1810 portrait by American painter John Wesley Jarvis, from the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. There are other images of him in existence, but this is certainly the finest painting ever made of him, and it is from the period that we cover in this podcast episode.

Thomas Cooper was an actor who had great success on both the London and on the American stage. After an initial success at Covent Garden in the 1790s, he came to America and quickly became a sensation in both Philadelphia and New York, but he infuriated the Chestnut Street Theatre's management by breaking his initial agreement with them. In the long run, though, his talent was too great for them to do without his performances, and he appeared on the Philadelphia stage many times in his life. Always restless and highly ambitious, he often dashed between New York, Philadelphia and other American cities in the period 1796 to 1802. Sometimes, for a stunt, he would appear in New York and Philadelphia on consecutive nights - making an arduous 95-mile journey over both land and water. From 1802 to 1804 he returned to London again, and during this period he did several performances with George Frederick Cooke in Othello at Drury Lane. During his prime years, he was much admired by female patrons at the Chestnut Street Theatre, and was referred to as "The Divine Cooper".

He became co-lessee of the Park Theatre in New York in 1810, and was given the responsibility by his partner Stephen Price for recruiting actors from England. On his first trip he hooked a very big fish indeed, and returned with his catch: George Frederick Cooke. The financial success of sponsoring Cooke's tour helped to make Cooper a fortune.

Despite the social stigma of being a mere actor, his financial success allowed him to wed Mary Fairlie, a New York socialite. The Cooper family lived in a grand mansion on Broadway in Manhattan. However, Cooper was eventually to lose most of his money in the great Panic of 1837. To save the family's fortune, his daughter Priscilla also became an actress, and while performing in Richmond, Virginia, she met and married Robert Tyler, the son of a US senator from Tennessee. When that particular senator later became the principal resident of the White House in 1842, Priscilla acted as President John Tyler's official hostess - essentially the Acting First Lady. Using this close connection to the Tyler Administration, in his final years Thomas Cooper managed to obtain a political patronage job, administering the customs offices at the ports of New York and Philadelphia. He died in Bristol, PA in 1849.

Below is an engraving of the playwright, theatrical producer, historian and painter William Dunlap (from the University of Illinois theatrical print collection). A native of Perth Amboy, New Jersey, the multi-talented Dunlap has appeared several times in our story, and was very important in both the early theater history of Philadelphia and New York. In 1811 he was a bit down on his luck, having failed as a playwright and producer. As we detail in the episode, he was assigned by Cooper and Price to look after Cooke during his travels. He did so faithfully, although his patience was often tried to the fullest by Cooke's antics. Before his death, Cooke gave him the authority to write his complete biography, and gave him access to his books and his diaries.

But Dunlap really wanted to be a painter, and in fact had studied with Benjamin West as a young man. Although he also wrote a history of early theater in America, he is best known nowadays for his three-volume History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, and for helping to found the National Academy of Design.

Here are two contemporary prints of the grave of George Frederick Cooke in the cemetery of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Manhattan. In one, Edmund Kean is shown next to the grave after donating the funds for it. The other print shows the wrought iron fence which was placed around the monument to protect it in the 19th Century.

The monument's stone has deteriorated over the years, and subsequent generations of actors have tried to maintain it. A metal plaque was attached in the 20th Century. Note that Keane's name is almost as big as Cooke's in the billing!

"Three kingdoms claim his birth" in the inscription refers to England, Ireland and Scotland. But in truth we don't really know where Cooke was born. Possibly he didn't really know himself, although he later insisted that he was born in Westminster, England. He could also have been born in Dublin, Ireland, where his father may have been stationed in the Army. It's unlikely that he was born in Scotland, although he did grow up in Berwick-on-Tweed, which is quite close to the Scottish border. Perhaps his facility with the Scots dialect led people to believe he may have been Scottish himself.

His mother, by several accounts, was a "willful and strong-minded woman" who may have run away with a soldier against her family's wishes. His father is not much mentioned in accounts of his early life, and it's not clear if his mother died or if she was mentally unstable and unable to raise a child (perhaps his bipolar tendencies were inherited, but again, that is just conjecture on my part). At some point he was passed on to relatives, and young George was raised by his mothers sisters in Berwick.

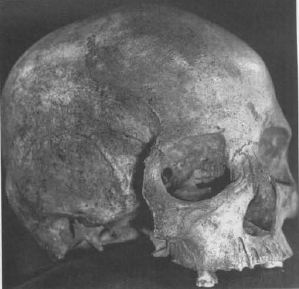

Below, finally, is the actual skull of George Frederick Cooke, now in the collection of the Library of Thomas Jefferson University (the image is from archival documents - again, the item is NOT on public display).

It seems that Dr. William Francis also made a 'death mask' of Cooke after his patient died. This artifact is currently in the Theatre Collection of Harvard University Library. A photo of this death mask, and also a photo of the third Thomas Sully portrait of Cooke, can be viewed on the Patreon blog for this - but for Patrons only. Please consider becoming a supporting member of the show there if you'd like to see them, and much much more additional supporting material about Philadelphia theater history. https://www.patreon.com/AITHpodcast

Excitingly, I have been informed by F. Michael Angelo, the Archivist and Head of Historic Collections at Thomas Jefferson University's Scott Memorial Library that the theatrical career of his skull may not be over! He has plans to make a scan of it, and to license it for 3-D printing. Theater companies who require a skull for Yorick in a production of Hamlet could digitally download the skull, and use it for a prop! Please get in touch with him if that's what you're in the market for!

The only way to end this post is by quoting a line from the play with which Cooke made his Philadelphia debut, back in March of 1811: "Off with his son George's head!" - Shakespeare, Richard III, Act V, sc. 4.

Selected Bibliography:

Bernard, John, Retrospections of America, 1797-1811, Harper and Brothers, New York, 1887, pp. 364-374. Digitized 2012 and available via Google Books.

Bowers, Rick, "Shakespearean Celebrity in America: The Strange Performative Afterlife of George Frederick Cooke," Theatre History Studies, vol. 31, 2011, pp. 27-50 (article). Published by The University of Alabama Press.

Dunlap, William, History of the American Theatre, J. & J. Harper, 1832, pp. 384-393. Digitized 2009 and available via Google Books.

Dunlap, William, Memoirs of the life of George Frederick Cooke, Esquire, late of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, In two volumes, New York, 1813.

Durang, Charles, History of the Philadelphia Stage, Between the Years 1749 and 1855. Volume 1, pp. 287-302. Arranged and illustrated by Thompson Westcott, 1868. (Available online courtesy Penn Libraries, Colenda Digital Repository)

Fennell, James, An Apology for the Life of James Fennell, Written by Himself, Philadelphia, 1814, pp. 393-397, 405-410. Digitized by Google Books 2008, available on the Internet Archive.

Hare, Arnold, George Frederick Cooke: The Actor and The Man, The Society for Theatre Research, 1980.

Johns, Christopher M. S., "Theater and Theory: Thomas Sully's 'George Frederick Cooke as Richard III' ". Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Spring, 1983), pp. 27-38. Published by University of Chicago Press. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1180790

Legend and Lore: Jefferson Medical College, Chapter 14 - Archival Objects, March 2009, pp. 641-660. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/savacool/15

Wilmeth, Don B., George Frederick Cooke, Machiavel of the Stage. Contributions in Drama and Theatre Studies, Number 2, Greenwood Press, 1980.

Wood, William B., Personal Recollections of the Stage, Embracing Notices of Actors, Authors, and Auditors During a Period of Forty Years. Philadelphia, 1855, pp. 89, 134-170. Digitized 2008 and available via Google Books.