As additional information about John Arneaux, here is the sheet music for his song "Jumbo the Elephant King". It is in the collection of the Library of Congress in Washington DC. (Arneaux appears to have written at least two other songs, "You Had Better Ask Mama" and "She is a Darling, If You Did But Know It", but their sheet music apparently has not survived.)

It is not known that John Arneaux himself ever worked for a circus, but he sees to have known the man who was the valet for Philadelphia circus impresario Adam Forepaugh, as we can see from this small social item printed in T. Thomas Fortune's New York World on June 23, 1883:

But it is telling that Arneaux's friend was a valet to a wealthy man. We should not forget how limited were the areas of American business that Black men could enter, in this era. If they had the education or ambition to be something above common laborers, just a few areas were open to them: valets, waiters, cooks, railway porters, preachers, minstrel show performers - and barbers.

In March of 1883, as we mention in the episode, Arneaux opened up a barber shop in New York's theater district. The prose of the advertisements he placed in the New York Globe give some idea of his prose style:

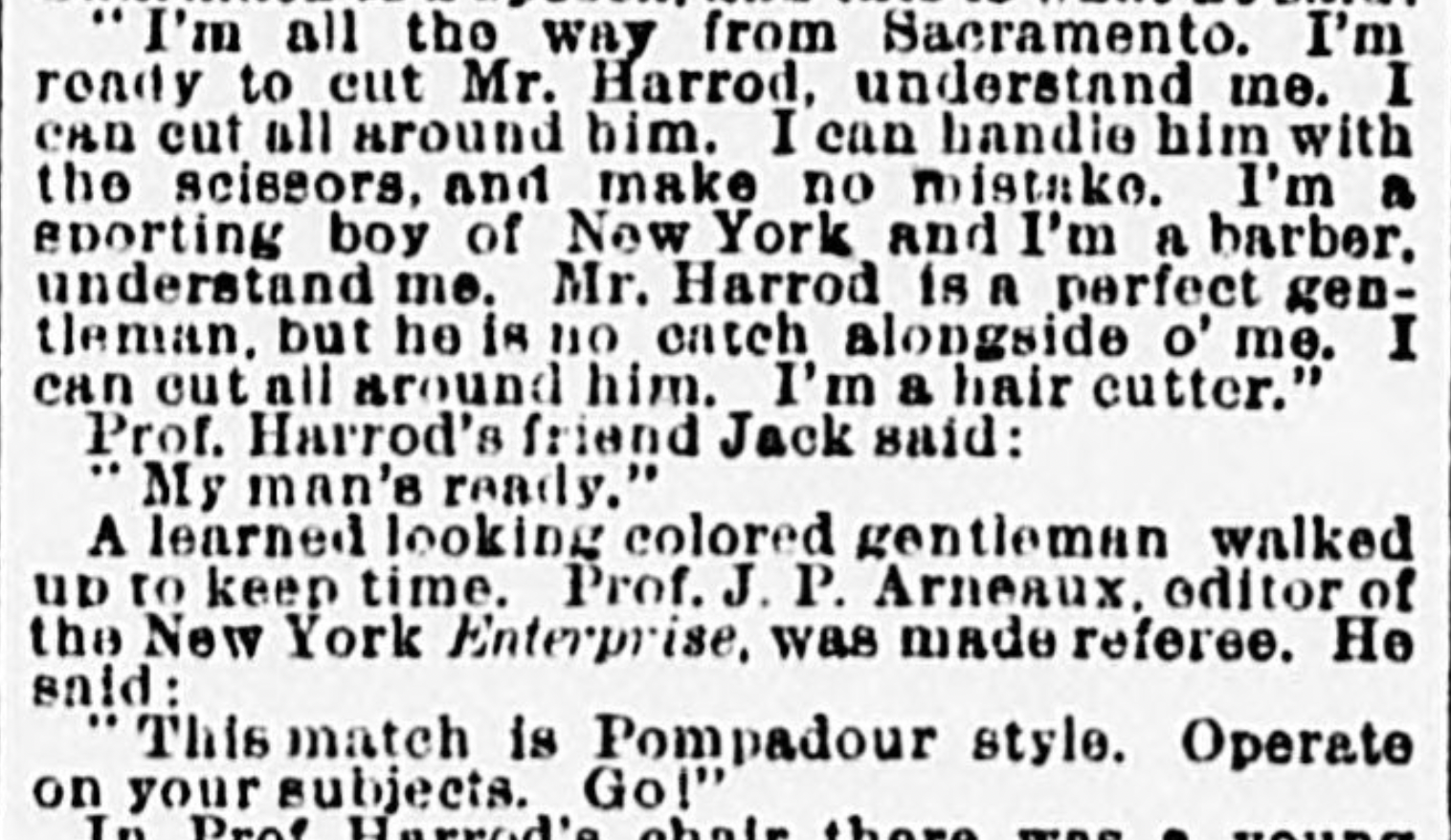

One other interesting tidbit that I was unable to work into the podcast episode - in April of 1886 the New York Sun published a light article about a supposed duel between two white barbers in New York City. $250 was at stake, if either man could artfully cut a gentleman's hair in a particular style in the shortest amount of time.

Interestingly, John A. Arneaux (who, if he were not misidentified as "J.P. Arneaux" I would have said may well have been the author of the article) was called in to be the impartial referee:

The New York Times also covered this hair-cutting contest, and named Arneaux as the referee. It is interesting to note that no one objected to a colored man being the final arbiter. It seems that in this era, male barbershops were regarded as the natural province of Black men - being one of the few businesses in America where they had long had dominance.

Anyway, for our purposes, it is worth noting that even as J.A. Arneaux was pursuing his journalistic and theatrical careers in New York of the 1880s, he was still a well-known and impressive authority figure in yet another profession. His own striking appearance, including the well-cultivated mustache we can find in every surviving image of him, was based on deep experience in the 'tonsorial arts'.

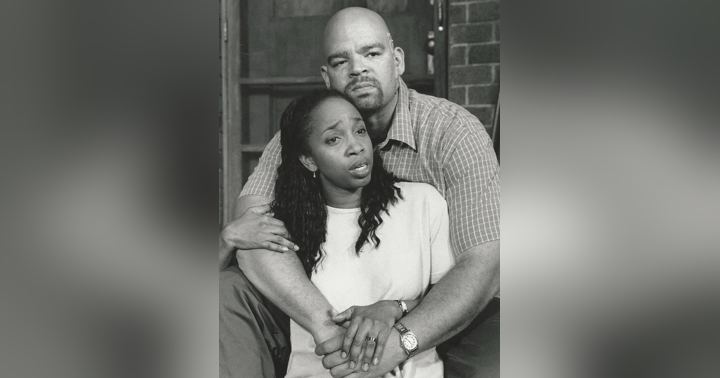

We end with one of the few surviving images of Arneaux, an engraving based on a photograph (which is sadly lost), that was printed in the edition of Richard III he self-published in 1887. He can't have cut his own hair, of course, but one can note that his own personal grooming was elegant and beyond reproach.