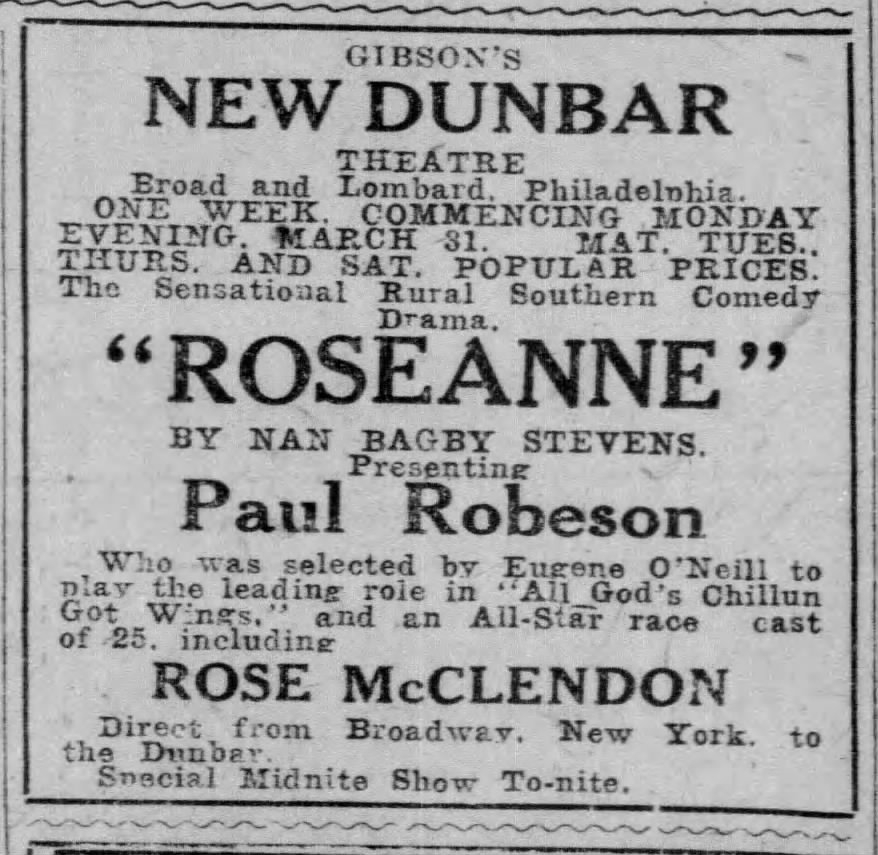

By the time the above photo was taken, Robeson's history in Philadelphia stretched almost fifty years. Below, an ad that appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, March 30th, 1924, marking Paul Robeson's first appearance on stage in the city.

Robeson's co-star in the drama was the great actress Rose McClendon, who would go on to be a significant figure in the theater herself thereafter - most of the buzz in the air that spring was about him. When he was finished with Roseanne, he returned to New York and appeared in two Eugene O'Neill plays at the Provincetown Players: All God's Chillun' Got Wings and The Emperor Jones. The success and notoriety Robeson gained from these two shows made him a major force in American theater and society. For the next fifty years the country would continue to struggle with the implications of his overwhelming talents, coupled with his strong political convictions.

True, the white Philadelphia press often did not seem to know what to make of him. Although he had grown up in neighboring New Jersey, the Inquirer puzzlingly referred to him in print as "the famous English negro actor." (In another article they misspelled his name as "Paul Edeson".)

The evening had begun with an address by the New York critic Heywood Broun, in the course of which, reported the Inquirer, Broun hailed the recent growth of American theater. "He said it was his opinion that the last five years in America is far better in its interpretation of human events and understanding than anything that was produced in the hundred years previous."

Well, it would take another eighteen years, but the answer to that question was Yes.

PART TWO: STRIVING

In October of 1949, by which point he was becoming increasingly politically active and controversial, he spoke and sang at another concert in Philadelphia's Metropolitan Opera House, which was packed with 4500 listeners. Though his appearance in Peekskill, New York, a few weeks before had sparked a violent riot against his fans by right wing mobs, there were only 200 anti-Robeson protestors on the sidewalk outside on Poplar and Broad St.(Photo from Temple University Libraries, Special Collection Research Center)

PART THREE: "SPEAK OF ME AS I AM"

In October of 1943, the long-awaited Theatre Guild production of Shakespeare's Othello, directed by Margaret Webster, played the Locust St. Theatre in Philadelphia, in preparation for an eventual Broadway production. Webster played the role of Emilia. Jose Ferrer and Uta Hagen, then married to each other, played Iago and Desdemona. It was a reprise of a cast which had gathered high praise in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Princeton, New Jersey the previous year. The sets, costumes, and lighting for Robeson's Othello were all done by Robert Edmond Jones, who had created the designs for so many other Theatre Guild productions (including The Emperor Jones.)

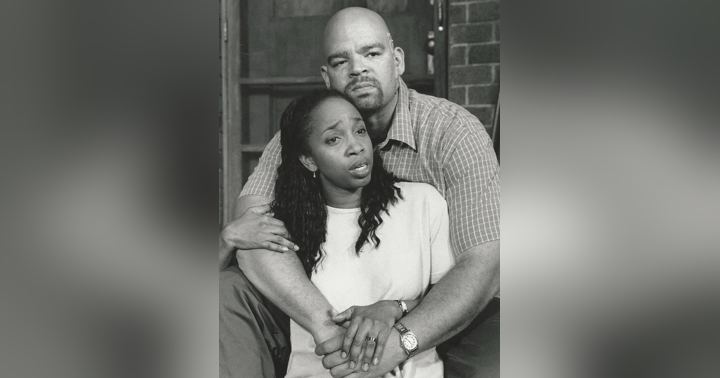

A photo of Robeson with co-star Uta Hagen appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, for its part, ran this photo from the play, showing The Moor right after slaying his wife.

There was less evident public uneasiness about the inter-racial casting than there had been two decades earlier, when the Black actor had played the husband of a white wife in All God's Chillun'. "Robeson is certainly the ideal Othello for the eye and ear," wrote the Inquirer's Linton Martin. "With his stalwart physique and his rich resonant baritone voice to give full value to the Bard's lines." (Perhaps, of course, if the secret affair between Hagen and Robeson had been more widely known, it might have been a different matter.)

The production of Robeson's Othello went on from its Philly tryout to have a famously long and triumphant run in New York. Groundbreaking in its day, it has remained perhaps the most successful production of the play ever done on Broadway.

PART FOUR: GOING HOME

(Image from the collection of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division)

As the above document details, Robeson was blacklisted and unable to travel abroad for seven years, starting in 1950. Local Philadelphia papers largely turned against him, and even many other Civil Rights Movement activists warily avoided contact with him. But after the restoration of his US passport in 1958, Robeson traveled the world as he had before. He went everywhere from London to Israel to Australia and New Zealand. He performed Othello again - this time in Stratford-on-Avon itself with the Royal Shakespeare Company. He continued his political and social activism as well as his concert performances. He vociferously, and perhaps unwisely, continued to be a vocal supporter of the Soviet Union, even after its own leadership had revealed the depths of Stalin's crimes. He was even interested in new 'freedom fighters' who spoke out against colonialism, like Fidel Castro.

But after announcing plans to travel to revolutionary Cuba, Paul Robeson suffered a catastrophic mental health breakdown in a Moscow hotel room in 1961. He attempted suicide by slashing his wrists. (His son Paul Robeson Jr. was openly suspicious that his father had been drugged with hallucinogenic drugs, and that his mental collapse had been part of a plot by the CIA and MI6 to prevent Robeson from being present in Cuba during the Bay of Pigs invasion.) Numerous stays in sanitariums around Europe followed - including a disastrous one in London where too many electro-shock treatments were administered and too many drugs prescribed. Robeson returned to the US in 1963, a broken man. He lived for a while with his son's family in New York, but after many distressing incidents, it was decided that the best solution was to have him stay with his sister in Philadelphia. He seems to have first visited Marian for an extended time in 1966, and moved to West Philadelphia permanently in 1968.

Below, a photo of Marian Robeson Forsythe and her daughter Paulina, who was grown and living with her own family nearby when her Uncle Paul arrived. This image is courtesy of the Paul Robeson House and Museum website. A full account of Robeson's final years in Philadelphia can be found there:

https://www.paulrobesonhouse.org/history-of-robeson-house/

Below, a photo of Robeson on his 75th birthday party, April 9th, 1973. (Again, the image is courtesy of the Paul Robeson House and Museum)

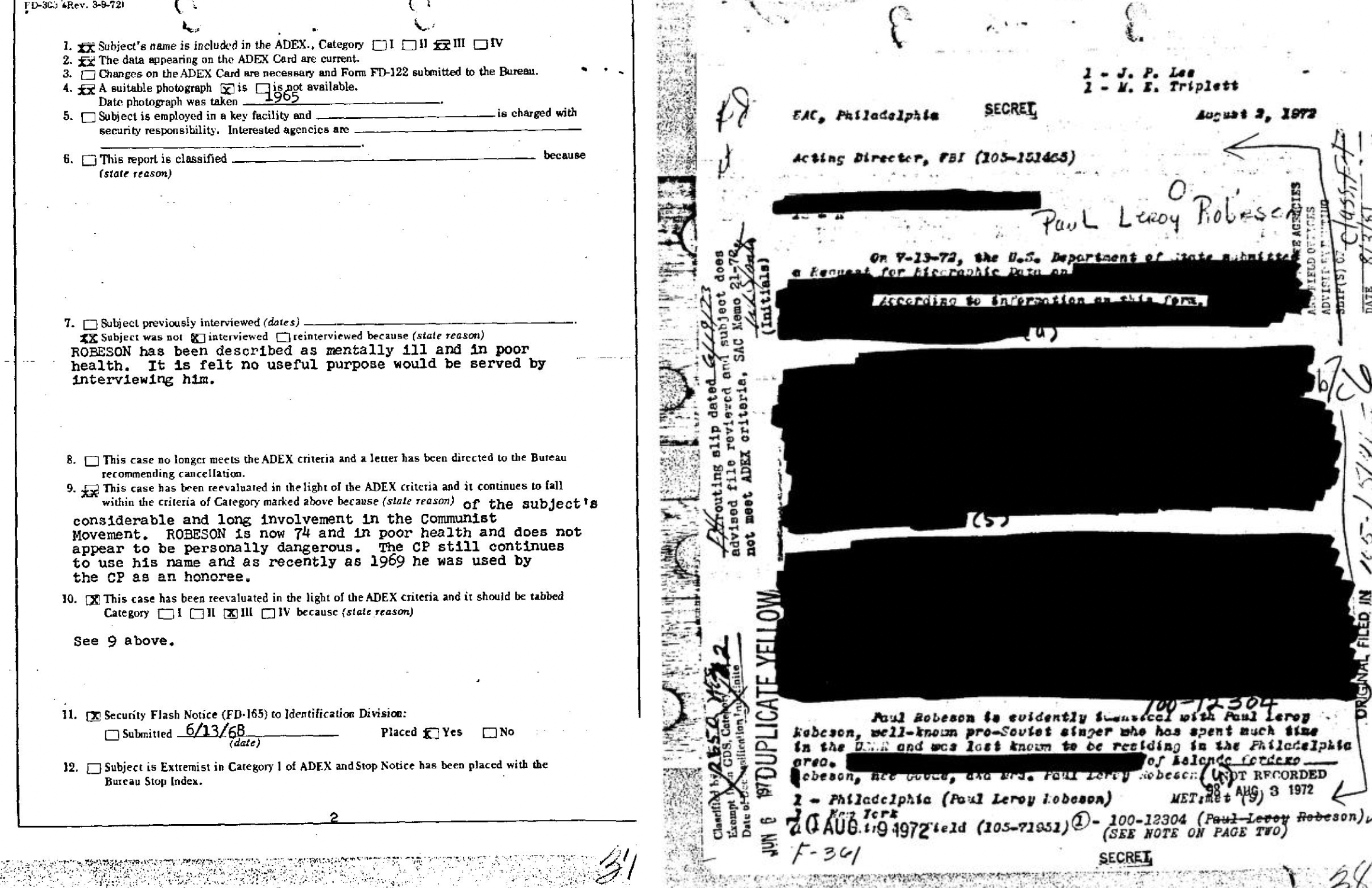

As we mention during the podcast, despite his obvious ill health and his complete absence from public life, the Federal Bureau of Investigation continue to monitor and surveil Paul Robeson as he lived in his sister's home in his final years. The entire FBI dossier on Robeson was later released under the Freedom of Information Act in 1981. It can be found online here: https://archive.org/details/FBI-Paul-Robeson/100-HQ-12304-01/

What is just amazing is how often the FBI's own documents show how old and ill Robeson was, and yet they continued to fear him as a 'symbol' or a rallying point for other 'radical' organizations. Often huge blocks of text are blacked out in the files - mostly apparently the names of informants within the various Philadelphia leftists groups the FBI had infiltrated.

Finally, here are three of the amazing women that we spend so much time either discussing or talking to during the podcast episode! Left to right: The late Francis Aulston, Terri Fimiano Guerin (in a photo taken inside the house as she was giving me the tour), and Janice Sykes-Ross. We are very grateful to all three of them!