An illustration by white artist Charles Bird King of a War Dance, performed by a delegation of Native American Tribes to Washington DC.

The illustration is the frontispiece of Volume One of McKenney's History of the Indian Tribes of North America. This is an intriguing example of an attempt at a respectful depiction of Native American dance, and it might be quite similar to those dance performances that we describe in the episode, which often included a War Dance.

Thomas Lorraine McKenney (1785-1859) is a figured with a historical legacy that might best be described as 'mixed'. A Quaker from Maryland, he served as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs from 1824 to 1830. As such, he was responsible for dealing directly with delegations coming from Indigenous people to Washington DC, and he took it upon himself to accurately record their lives and appearances. However, he was also an advocate of "civilization" programs, which sought to teach Indian bands the ways of white society, and also actively supported the forced removal of many nations across the Mississippi River. Nevertheless, he clashed strongly with the incoming Jackson Administration in 1829, because of his position that Cherokee lands and property should be respected, and for his views that in general "the Indian was, in his intellectual and moral structure, our equal." Dismissed from office by President Jackson, McKenney spent the remainder of his life writing, compiling and publishing the book for which he is most well-known. (And of course Andrew Jackson went on to perpetrate the hideous Indian Removal policy for which he is infamous.)

A few of the illustrations from the book are truly instructive at giving us both a picture of how Native people looked and behaved, in a manner quite different from those of the plays and actors that we discuss in our podcast. Here, for instance, is a portrait of Push-Ma-Ta-Ha, the Choctaw warrior who features so prominently in the life story of Edwin Forrest (as we detailed in Episode 13). He is not the 'child of nature' that he is portrayed in Forrest's account, but dressed in the blue coat and epaulets of an American general.

Some other interesting portraits from McKenney's book, which might give us a better idea of what visiting Native Americans to Philadelphia looked like in the early 19th century, can be seen in a portrait of a Shawnee chief named Qua-ta-na-pea, and an Osage woman named Mo-hon-go and her child.

Now that we have seen Native people portrayed with some dignity and respect, let's return to one particular instance when they were not. In our podcast's Episode 7, we discussed at length a painting by John Lewis Krimmel (now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York), and we mention it again in this episode. Remember that we concluded previously that this image is not intended to illustrate AT ALL an actual performance of Native American dance that took place at the Olympic Theatre (later the Walnut Street Theatre) in 1812. Rather, it just refers obliquely to an earlier dance performance at the Chestnut Street Theatre, and is actually a rather silly and smutty joke about what happens when your loincloth comes loose while you're dancing. The figure on the stage is the embarrassed performer, and the other figures are regarding him with reproach, mockery, or amusement.

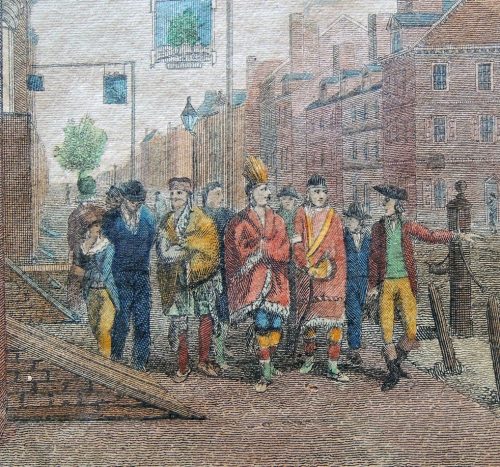

However, as we have stated, we can consider much better images of Native delegations actually visiting Philadelphia from the book Birch's Views of Philadelphia. First, in a detail from one such illustration, is an view of the group on 4th Street near the Lutheran Church:

Birch's picture of another Native delegation crossing the State House lawn, quite nearby to where the group might possibly have gone to see a show at the New Theatre on Chestnut Street, is here:

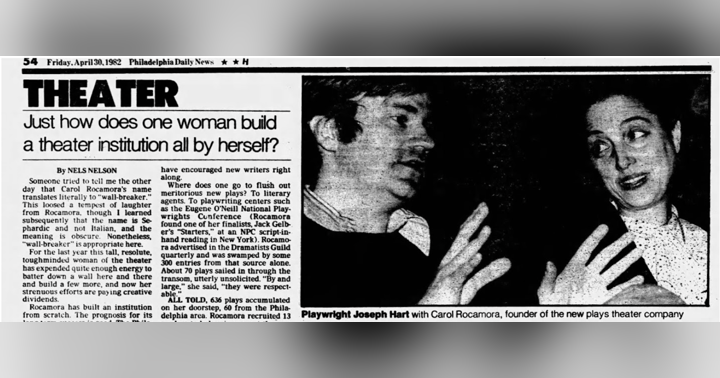

Above, advertisements in Philadelphia newspapers for dance performances by Native American delegations in local theaters.

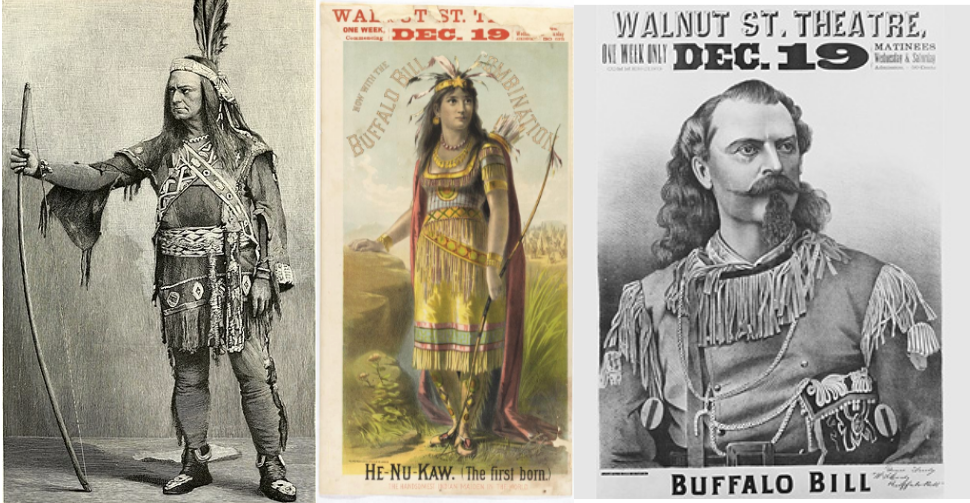

Below, Edwin Forrest in costume as Metamora, and posters from Buffalo Bill's shows at the Walnut Street Theater in the 1870s:

Above, Buffalo Bill and his troupe in front of Wanamaker's Department Store in Philadelphia, 1908.

I'm also delighted to share with you some images of Caroline "Gowongo" Mohawk, whose name translates, she always said, to "I Fear No One" - thus giving us the title of the episode. I first came across her image and a 1891 newspaper clipping in a theatrical scrapbook that is in the collection of the Kislak Library of the University of Pennsylvania. I was looking for something else at the time, but I'm so glad I quickly took a picture with my phone of her printed image and an accompanying newspaper story about her, possibly from the Evening Bulletin. This find later gave me a lot of inspiration for this entire podcast episode.

There are other images of Gowongo Mohawk that I have subsequently found elsewhere online. I especially like the publicity photo of her in a fringed jacket, signed "Aboriginally Yours!"

One additional note: Throughout this episode, I strive as much as possible to use the term "Native American", when referring to people of Indigenous ancestry as a whole. When appropriate, I employ the specific name of the tribe or Nation involved. At other times the term "Indian" is used because that is the word used in every source document from this period, even by Native people themselves. I am aware that there is not a clear consensus on this terminology, even today.

But it's an odd term to use specifically in the context of Philadelphia history of the 19th Century. As you may or may not know, there was a powerful political movement in Philadelphia in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s that also used the term "Native American". These were generally Protestant white Philadelphians who were opposed to Irish immigrants, and Catholicism in particular. Feelings reached a fever pitch in 1844 when riots broke out in the city and also in the townships of Frankford and Southwark. Churches were burned, the local militia was called out, and there were open gun battles in the streets. "Native American" had a very different context back then. But as those events are mostly forgotten today, I will stick to the current nomenclature.

In the podcast, we mention the difficulty with uncovering ancient Lenape artistic and spiritual practices in Eastern Pennsylvania. There are organized Delaware nations today in Oklahoma, Ontario, and Wisconsin. But some descendants of the Lenape are still resident in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which does not recognize ANY organized Indigenous Nations within its borders. A good article on the subject is here: https://whyy.org/articles/we-just-want-to-be-welcomed-back-the-lenape-seek-a-return-home/

The writer and blogger "TravSD" had devoted a LOT of space and thought to the subject of Native Americans and show business in the USA. I highly recommend checking out his many entries on his website. A good place to start is here:

https://travsd.wordpress.com/2021/11/01/a-project-for-native-american-history-month-and-the-first-thanksgiving-quadricentennial/

Selected Bibliography:

Calloway, Colin G., “Urban Encounters”, History Today, July 2021, Issue 7, pp. 66-75.

Calloway, Colin G., The Chiefs Now In This City, Oxford University Press, 2021.

Fees, Paul, “Wild West Shows: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West”, online article at Buffalo Bill Center of the West website. https://centerofthewest.org/learn/western-essays/wild-west-shows/

Holmes, Chris, “Vintage Photo Wednesday, Vol. 40: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in Philadelphia, 1908”, online blog article at grayflannelsuit.net https://www.grayflannelsuit.net/blog/buffalo-bills-wild-west-in-philadelphia-1908

Hughes, Bethany, “The Indispensable Indian: Edwin Forrest, Pushmataha, and Metamora”, Theatre Survey, Volume 59, January 2018 , pp. 23-44.

Jones, Eugene H., Native Americans as Shown on the Stage: 1753-1916. The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen NJ, 1988.

Lepore, Jill, The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. Knopf, New York, 1998.

McKenney, Thomas Lorraine, History of the Indian Tribes of North America, Philadelphia, 1838. Accessed online via The Newberry Library.

Otis, Melissa (2017). "From Iroquoia to Broadway: The Careers of Carrie A. Mohawk and Esther Deer". Iroquoia. 3: 43.

Quinn, Arthur Hobson, A History of American Drama, From the Beginning to the Civil War, Harper and Brothers, 1923, pp 203-245.

Wood, William B., Personal Recollections of the Stage, Embracing Notices of Actors, Authors, and Auditors During a Period of Forty Years. Philadelphia, 1855. Digitized 2008 and available via Google Books.