The story of three small ambitious cutting-edge Philadelphia theater companies of the 1970s. Why did some survive - and some falter?

The story of three small ambitious cutting-edge Philadelphia theater companies of the 1970s. Why did some survive - and some falter?

Here’s a special opportunity for those of you who are in the Philadelphia area: on Wednesday, April 9, 2025, I will be moderating Curtains Up on “Cato” - A Panel on Revolutionary Theater. a panel of distinguished scholars in the Alan B. Miller Theater at the Museum of the American Revolution on the corner of Third and Chestnut, from 6-8 p.m.

The panel will include Dr. Shawn David McGhee of Temple University, Dr. Chelsea Phillips of Villanova University, the author Eli Lynn, and the dramaturg Chazz Martin!

Adventures in Theater History podcast listeners are invited to receive the reciprocal Museum of the American Revolution member discount for this special program. Go HERE, select $15 Museum Member and (as your Registrant Details) please enter the code: REMIXED

"Adventures in Theater History: Philadelphia" the BOOK can be ordered from independent bookstores and at all online book retailers now!

To see a listing on Bookshop.org - GO HERE

IF YOU LIKED THE SHOW, AND WANT TO LEAN MORE:

Our website: www.aithpodcast.com

Our email address: AITHpodcast@gmail.com

Bluesky: @aithpodcast.bsky.social

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AITHpodcast

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aithpodcast/

YouTube: @AdventuresInTheaterHistory

Support us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/AITHpodcast

© Podcast text copyright, Peter Schmitz. All rights reserved.

℗ All voice recordings copyright Peter Schmitz.

℗ All original music copyright Christopher Mark Colucci. Used by permission.

© Podcast text copyright Peter Schmitz. All rights reserved.

Hello, everyone. Welcome back to Adventures in Theater History, where we bring you the best stories about the deep and fascinating history of theater in the city of Philadelphia. I’m your host Peter Schmitz. Our original theme music is by Christopher Mark Colucci.

In New York theater parlance in the late 20th Century there used to be an interesting hierarchy of theatrical performance. There was “Broadway,” of course, mainstream big commercial productions that were offered in a specific set of Midtown theaters. There was “Off-Broadway” - those smaller professional theaters (both commercial and non-profit) that mostly thrived in Downtown neighborhoods like the East and West Village, although a few were elsewhere. Then there was something called “Off-Off-Broadway” which could happen literally anywhere else in the city, and could be either professional, semi-professional or unpaid work. These were mainly experimental or cutting edge theatermakers, existing off of grant money, or just from their day jobs. But of course with all three of these, actual proximity to the long diagonal avenue that travels the length of Manhattan - Broadway - really had nothing to do with it.

Today, in a Philadelphia context, I’m going to talk about “Off-Off Broad Street.” I’m going to talk more specifically about three small, even tiny, Philadelphia non-profit theater groups in the 1960s and mostly the 1970s that eventually became larger producing organizations in the 1980s, 90s and early 2000s. Sometimes these groups worked on the great central avenue that is Philadelphia’s Broad Street, but, you know, mostly not. But again the geography is not really the issue here, it is the tiny size of these groups budgets, which was inversely proportional to their enormous artistic ambitions. In some cases these ambitions laid the beginnings for a long-term theatrical institution - in most cases, however, the successes were beautifully transitory and had to be experienced at that particular moment, just like theater itself.

This mostly narrative podcast episode is in preparation for additional interviews with folks I’m hoping to have ready for you in subsequent episodes in the coming months. Now, I don’t want to get too deep in the weeds about this topic entirely, because I’m just not sure how deep into my research notes I want to carry all of you. There were quite a few small community theaters, non-profit companies, and independent producers from the 60s and 70s. I’ve even made myself an interactive map online of the street grid of Philadelphia, with annotations about where each one worked and performed over the years. That’s just for me, really. It’s just too much to share in audio form, frankly.

So let’s try something else.

April 16, 1973: An article appeared in the Philadelphia Daily News, reporting on the founding of a new theater/art group called "The Wilma Project." It was created by women, with a view to centering the experiences and lives of women. The feminist movement was then so much of the zeitgeist, in an era when Betty Friedan and Gloria Steinem were household names.

Ironically, however, the article about the Wilma Project shared the page with advertisements for X-rated films at Philadelphia's many, many pornography theaters: Love, Swedish Style, Black Madam, and The Maids (and that latter was definitely not a version of Jean Genet’s play - although, you know, he might have enjoyed it). Of course, this openly raunchy commercialization of human sexuality in the movies was another aspect of the early 70s zeitgeist, and these two things lived rather uneasily side by side.

So let’s go back to this deliberately feminine name “Wilma” - this was a nod, of course, to author Virginia Woolf’s famous essay “A Room of One’s Own,” in which she imagined a sister to William Shakespeare named “Judith.” This Philly group chose to take instead a variant of Shakespeare's first name, William, and make it “Wilma.” The second word of their title was a tribute to another theater group that they respected a lot - The Baltimore Project - which had recently been founded in Philly’s big city neighbor to the south. So: Instead of the Baltimore Project, “The Wilma Project.”

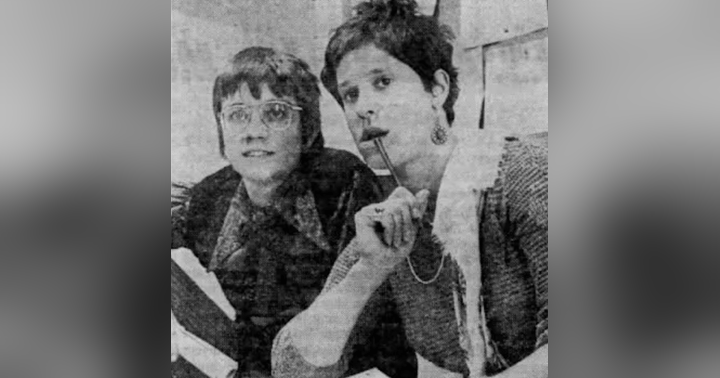

Jonathan Takiff’s article was accompanied by photographs taken by Charles Myers, and they showed two young women with closely cropped hair - and again that was unusual in the fashions of the early 70s. Liz Stout (age 25) and Linda Griffith (age 22) were shown in these photos. Also named, but not shown, was the sculptor Laurie Angheld. Jonathan Takiff reported that the art collective would open on May 9th in the parish hall of Trinity Memorial Church, 2212 Spruce Street in the Rittenhouse Square area.

"We have to share the auditorium space with a daycare center and a boy scout troop," said Griffith in the article. "At least we're guaranteed an audience," she said wryly.

What kind of work did they want to create? Not realism, said Griffith to the reporter, and not the absurdism of Beckett and Ionesco either. She was more inspired by female artists such as Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf.

"By virtue of the fact that we are women, and are doing women's work," said Stout, "we are feminist oriented. But women's lib is actually irrelevant to the aesthetic. We'd like to be Philadelphia's answer to La Mama [in New York]"

Now, although they used improvisation in their development and rehearsals, "compared to the Living Theater, we're a reactionary group. They stress spontaneity for its own sake. We're looking to be the opposite, to be the development of theater as craft, a discipline. The threat of film and television to the future of live acting insists on that."

The two’s first performance piece would be a new work written by Stout and directed by Griffth, called Elsie's Culpa: An Ontological Farce, which they described as a "modern morality play with religious implications.” The play’s plot centered around two women in a garden. One of them, Elsie, wakes up with a cup stuck on her elbow. Her friend, Lucille, enters and is full of advice about how to deal with this unwelcome protuberance, but it's Elsie who must ultimately work out her problem.

A subsequent article in the Daily News detailed how the group also planned to offer workshops, art shows, concerts, and dance pieces, amateur nights and street fairs for the surrounding neighborhood - but (and this is a key point) it did not plan to sell tickets. "There's a special rapport created between [the] performers and audience at free theater," said Griffith. "The actors have been conditioned to the fact that they won't be making much money . . . and the audience is put in the position of just having to respond to the work. Most stick around after the show, to rap with the performers. That's the biggest gift they can give. ."

Future plans included hosting mask making sessions, folk music acts, dance companies, and puppet shows. A summer workshop for children was also in their plans.

But the Wilma Project’s mission changed over the years - mostly becoming a venue for other small nonprofits - in the area or from outside the area - who needed a performance space. And hey, they had one! Dance companies, puppet theater, mimes, medieval music ensembles all came to 2212 Spruce - most of them for just a weekend.

As far as I can tell the two created just one more play - another absurdist feminist drama called Fever Dreams in Charlie’s America. What the play action was is unclear to me - just from the description in the reviews, there seems to have been one actor in it who was costumed in a large paper suit, looking kind of like a gingerbread man, and another who was mostly undressed - but in an essentially tasteful and artistic way, stressed Griffiths. Some of the visiting dance troupes had attempted to integrate nudity into their pieces too. It was The Seventies, you know? Unfortunately, the landlord, Trinity Memorial Church - perhaps mindful of that boy scout troop - didn’t like this at all. The company’s lease to their parish house was not renewed and the group was asked to leave.

By 1976 the Wilma Project found what they called a more “broad-minded” landlord at the Christian association auditorium on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania at 36th and Locust Walk in West Philadelphia. And this soon became known as the place where the most cutting-edge theater in the city could be found - in May 1976, as most of the city prepared for the Bicentennial - as we detailed in our last episode - the Wilma Project was hosting a Washington DC troupe in an intense improvisational piece based on Tennesee Williams’ short play, Our Lady of Larkspur Lotion.

But because the Wilma Project was a “free theater” it had no box office income - therefore it had to be fierce in fundraising. And this was a key factor in its long-term survival. It was attracting a lot of financial support from the Pennsylvania Council for the Arts, from the National Endowment for the Arts and from the William Penn Foundation. Now, it’s not at all clear to me, just from looking at the newspaper stories that I can see, exactly who was running the Wilma Project in those days - I have heard, anecdotally, that Stout and Griffiths had had a personal falling out, and maybe they had left the group . . . I’m really going to have to dig through some different archives than the ones I’ve been looking at to find out. I’m not sure the original founders were still in charge - though this could be the case. Whoever was running it, they certainly weren’t eager to keep their names in the papers, for whatever reason. All press stories just say “Wilma Project Free Theater” - and no leaders or spokespeople were ever mentioned beyond that.

But it is clear to me that whoever these folks were running the Wilma, they really weren’t producing their own work but rather had become facilitators for bringing outside artists to town, and running workshops, often with these outside theater artists. Lots of exciting avant-garde American theaters were coming through on tours under the aegis of the Wilma Project, and again they emphasized ones with Women-empowering viewpoints, “hostessing” - they put it - “Festival Womanstyle” a collaborative effort of different groups from the United States and Canada came in, as well as mime festivals and workshops by local mime artist Dan Kamin.

In the spring of 1977, the Wilma Project hosted Stuart Finkelstein, who was one of the original founders of the Manning Street Theatre group (that I’ve written so much about in my book) and he had subsequently studied with Jerzy Grotowski in Poland, was leading workshops in Grotowski’s techniques for the Wilma Project. He also performed, as part of a group called the Collaboratory Theater, a piece of his own devising called Kaspar Hauser - about a young boy who had been kept in isolation for much of his life - this was under the sponsorship of the Wima Project, again - but it was conducted upstairs in one of the small loft performance spaces available for rental at the newly-renovated Walnut Street Theatre.

But by now the Wilma Project Free Theatre was homeless again. You know, it had mostly become an organization that wandered from office space to office space - mostly just a place to put a telephone, so it could fundraise and organize. It was finding venues where they could and importing all the fascinating out of town talent. They even briefly brought Charles Ludlam and the Ridiculous theatrical company - again to the small upstairs theater at the Walnut Street Theater. That was in December of 1977. And there he did his Professor Bedlam’s Educational Punch and Judy Show, a hysterical puppet for kids during the day, and then the decidedly more adult The Ventriloquist's Wife with his dummy Walter Ego in the evening.

By 1978, the Wilma Project had found another space, 1007 Filbert Street, north of the new Galleria Center City shopping complex along Market. But you know, Spalding Gray and the Performance Group would sometimes be featured there. Then they moved to a tiny storefront place on Bread Street in Old City, near where the Arden is now. Again, Wilma was still pretty good at fundraising, and even though they had no real home, they were starting to develop what they called a ‘resident acting company’ of Philadelphia actors, to do experimental theater pieces, and they had some success getting critical attention for those from alternative weekly newspapers. And sometimes they would even tour - they made a piece eventually about the Three Mile Island disaster, which of course had happened in the 1970s out in Limerick, to the west of Philadelphia. But still, it was mostly out of town groups that came in for the Wilma. Other well-regarded New York experimental troupes, like Ping Chong, were coming down to Philadelphia under the Wilma’s mantle.

In October of 1978, they advertised that they were offering another Grotowski workshop for that resident company and for, frankly, whoever wanted to pay some money and join in. This time, however, they didn’t mention who the teacher was - she wasn’t from out of town, she lived in the Philadelphia area, although she was an immigrant, technically - recently arrived from Czechoslovakia, in fact, and her husband worked in the film industry when he could. But in Europe she had studied with Jerzy Grotowski himself, and she, along with her husband, had lots of experience in avant-garde theaters in Prague. The couple had a nine month-old son, but by now this woman was kind of itching to get out of the house. She had seen an article about that production of Kaspar Hauser, and its connection to Grotowski, so she called the Wilma Project and said: “I’ll give you a workshop on Grotowski!” But she said she didn’t have a car. They would have to pick her up and drive her back out to Drexel Hill afterwards.

Well, okay, the Wilma Project folks said, that sounds fantastic, let’s do it. But, you know, they didn’t list her name in the ads. After all, Blanka Zizka . . . who was she?

Well we will pick up the story of the Zizkas and the Wilma in future episodes, you bet. But let’s now move on to the story of another small theater company, somewhat less attuned to the avant garde, and more interested in newly-written conventional plays and the classics.

On July 18, 1975: The Philadelphia Company presented Shakespeare's Twelfth Night at the Vasey Theatre on the campus of Villanova University in the suburbs to the west of town.

The organization had been formed the previous year by Villanova faculty member Robert Hedley and Jean Harrison. Hedley directed Twelfth Night and Harrison appeared as Olivia. Perhaps because they were performing in a rather remote venue in an otherwise deserted summer college campus, this production had some trouble attracting the attention of Philadelphia theater reviewers.

But the Daily News' Stu Bykovsky showed up, however, and wrote an effusive article about this production: " . . Twelfth Night is a good night."

Now just two years later, the ambitious young company had secured grants and permission to re-stage their Shakespearean comedy in the outdoor courtyard of Philadelphia's City Hall, where under the stars it played all month long. Some noted the incongruity of the setting amidst the seats of Philadelphia's notorious bureaucratic, grouchy (and corrupt) city government, which was not known at the time for its advocacy for the performing arts.

Twelfth Night was followed in the City Hall courtyard by Philadelphia Company's equally ambitious production of that old standby, the 18th Century comedy classic She Stoops To Conquer.

Now a lot of the information I was just telling you was originally written for my daily posts on Facebook and Instagram and Bluesky about Philly theater history - and folks, I wanna tell ya - I really love it when folks read these posts and share them, respond to them, and sometimes they correct me on some point of fact - or they add additional details. For instance, I want to thank David-Michael Kenney for sending me all sorts of material about this production of Twelfth Night. And I also want to thank Mark Lord and Jim Christy for giving me all sorts of details about these early years of the Philadelphia Company, which I hope to use when eventually I interview them.

So all that’s fantastic. But as I said, this nascent Philadelphia Company wasn’t just producing classic texts. That is why in January 1976: Four American playwrights took a walk in Philadelphia's Washington Square.

John Yinger, David Rabe, Pauline Jones, and Leslie Lee were all having their new works produced in the second season of the young Philadelphia Company, under the artistic direction of Robert Hedley. These works would be staged, again, in the small Theatre Five, up in the converted industrial loft building joined a few years previously to the Walnut Street Theatre at 825 Walnut.

For publicity purposes, a photo session had been booked in the nearby Washington Square park with a photographer from the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin.

The season would open in February, said the accompanying article, with the premiere of Marlowe, by John Yinger, which was billed as "an intimate portrait" of the Elizabethan poet, dramatist and spy. Yinger would then also act, along with the great Philadelphia actress Carla Belver in a play, Rain - a revival of a play from the 1920's, adapted from a story by W. Somerset Maugham.

An evening of one act plays was scheduled for March, which would bring together works of two of Hedley's colleagues at Villanova University, David Rabe and Leslie Lee. Rabe was already well known in those days, of course, for his plays about the Vietnam War, Sticks & Bones, and The Basic Training of Pavlo Hummel, as well as In The Boom Boom Room – which was set in a bar in the working class Northwest Philadelphia neighborhood of Manayunk.

Leslie Lee, who had grown up in West Conshohocken and was educated at the University of Pennsylvania, had recently received multiple awards the previous year for his hit play The First Breeze of Summer.

But on this event, Rabe and Lee were pairing two of their shorter works: The Crossing (about a young man's coming of age) and As I Lay Dying, A Victim of Spring (a comedy about the Second Coming of Christ).

The final production that was planned by the Philadelphia Company was to be a new translation of Eugene Brieux's 19th Century melodrama The Three Daughters of M. Du Pont, by Bryn Mawr professor Pauline Jones, and that would be staged in April.

But first, there was publicity to be done - so there was this walk in the park for the photographer. The four playwrights gamely linked arms, walked together along the flagstone path . . . . while the camera clicked away. And then they all stopped for a rest, and had a smoke.

As we have often mentioned, this was an era when many small and ambitious young theater companies were struggling to find their way in the city - and this was true in cities all over America. But you know, it was a hard time for big American cities generally, and for Philadelphia in particular, whose population and economy had been plunging for the past twenty-five years. You know, I was struck recently, when the great film director David Lynch passed away . . . all his obituaries mentioned that this was the era when he was living in Philadelphia, going to art school at the Pennsylvnia Academy of Fine Arts and making his early films in this grungy, abandoned and rather dystopian urban atmosphere - this post-industrial and crime-ridden Philadelphia. Now he loved it; he found real truth from that. But like David Lynch, some theatermakers found living here very inspirational, and yet others found it, not quite, on a human level, sustainable. So let’s talk about one other story: The Repertory Company.

The Repertory Company had been founded in 1974 by director Joe Aufiery, a recent graduate of The Neighborhood Playhouse in New York. Originally the Repertory Company had used a second floor space in a Powelton Village warehouse in West Philadelphia, but now had moved to a 100-seat basement theater in the basement of an office building in the middle of Philadelphia's Center City business district. The company had a core group of about 20 performers. And as another way of raising income, it offered classes in the evenings - they were called "Acting for Enjoyment".

In January of 1977: Barry Sattles and Daniel Oreskes played the two title roles in - again, Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz & Guildenstern Are Dead, presented by The Repertory Company at their space at 1924 Chestnut Street. This new small theater company could only afford to advertise their production with the most basic little tiny box ads in the Philadelphia dailies, although they had their following!

The production was very highly praised. Especially noted were the two actors playing the title roles, Sattles and Oreskes - and John Bleasdale, who did the Player King. Smaller roles were handled with less success - but at least no one was painfully bad, wrote Daily News critic Jonathan Takiff.

This production of “R&G” was restaged by the Repertory Company in June of 1977, and it was successful enough that again it was brought out in November of 1978, with Aufiery taking over the role of Player King. It was an era when Center City was kinda dead after 5 o’clock, and many people tended to avoid Center City in the evening. So the Rep tried something else, they would stage a lunchtime series of 40-minute long comedic plays for the city's office workers for as little as two dollars. Offerings included Murray Schisgal's The Typists, the medieval play Second Shepherd's Play, and the original work Bring In the Naked Girls (that must have been something!). But they would also do full-length productions in the evenings at their regular space: Our Town, Candida, Spoon River Anthology, A Flea in Her Ear, The Glass Menagerie, Caucasian Chalk Circle, Desire Under the Elms, and David Mamet’s American Buffalo.

In the spring of 1979, however, Joe Aufiery suddenly resigned - it was just "artistic differences," said a company spokesman to the newspapers. Aufiery wanted to hold more classes and stress education, and the rest of the company wanted to stage more plays.

But evidently that was not the whole story. Running a small theater company in a poor economy was inevitably stressful on the lives of young people that were trying to make this their career. "On my part, it's financial, totally," Aufiery himself told the Daily News in an interview, and said that budgetary issues had led to "emotional anxiety" on the part of a number of persons in the group. For the moment he was moving on, anyway. "I'm only 32 years old. There's a lot I have to learn about myself and about life. . . . At least I got a terrific girlfriend out of it" And Aufiery and the actress Margaret Lutz both left the company thereafter.

In 1980 the company was struggling to survive. It was still offering classes, but had mostly stopped presenting plays. In 1981 Aufiery returned to direct a production of David Mamet and Tennessee Williams. But in 1982 Frank Lyons, who had been the president of the organization for the past two years, regretfully closed the theater company, settled its affairs, and managed to pay off the last of its debts.

So that’s our story for today. For those of you who are into really deep cuts of small theater groups in Philly at the time, I realize I’m skipping over such Philadelphia theater groups as the Pocket Playhouse, the Society Hill Playhouse - as well as overlooking developments out in the suburbs like People’s Light and Theatre Company. I’m also still putting off discussing, for the moment, significant African American theaters like the Freedom Theatre in North Philadelphia and the Bushfire Theatre in West Philadelphia.

But . . . thanks for bearing with me. In the next month or so, I’m going to be pretty busy in my own professional life. And in May, I’m gonna be performing in a play! Let me tell you about it! It’s called Cato (Remixed). It is based upon the 1713 historic play Cato: A Tragedy by the English writer Joseph Addison. Very famous in its day! And it is famous in theater history circles as being "George Washington's favorite play."

This 18th century verse drama is about the Roman statesman - and updated to address our own current historical and social moment.

And it’s going to be performed, fascinatingly, in a historic site - under the aegis of the Philadelphia Artists Collective - the PAC - it’s going to be done in Philadelphia's Carpenters Hall, a building which was the site of the First Continental Congress in 1774!

Now in the show I am going to play Cato (the title character!) - but I will also be playing George Washington . . . and another character closer to my own self, a local theater historian. You know, type-casting. Anyway, that’s what I’m up to.

But I’ll keep up with my work here on the podcast as best I can. Soon I’m hoping to bring you an interview with Robert Hedley, that great figure of Philadelphia theater, who as we just discussed, was essential in the formation of the Philadelphia Theater Company. I talked with him a few months ago, I just need to get that sound file properly edited before I can get it back out to you.

But in mid-April 2025, please look here on this podcast feed for a special episode.

Now, remember that production of CATO I told you about? Here’s a special opportunity for those of you who are in the Philadelphia area: I will be "moderating" - that is, asking all the questions - to a panel of distinguished scholars of the theater, on Wednesday, April 9, 2025 in the Alan B. Miller Theater at the Museum of the American Revolution on the corner of Third and Chestnut, from 6-8 p.m, and this symposium is going to be called: Curtains Up on “Cato” - A Panel on Revolutionary Theater.

The panel will include Dr. Shawn David McGhee of Temple University, Dr. Chelsea Phillips of Villanova University, the author of the piece Eli Lynn, and the dramaturg Chazz Martin!

Adventures in Theater History podcast listeners are invited to receive the reciprocal Museum of the American Revolution member discount for this special program. All you gotta do is register at the Museum of the American Revolution ticket page for April 9, select $15 Museum Member and (as your Registrant Details) please enter the code: REMIXED - all caps. Now, in case you didn’t write all of that down, I’ll put these details again in the show notes to this episode.

I hope to see you there! Please let me know if you are coming and I'll look for you at the reception afterwards!

Indeed, if you have any messages for me, or any comments, or corrections - or praise! - write to me at aithpodcast@gmail.com. Or you can just use the “Contact Us” form on our website - www.aithpodcast.com. And you can also follow us, as I mentioned, on social media: Facebook, Instagram, Mastodon - Bluesky!

Meanwhile, if you haven’t gotten a copy already, look for Adventures in Theater History: Philadelphia - the book! And if you enjoy that, you leave a review on Amazon or Goodreads so that other good folks can learn about it, too. Yes you do! And you can leave a review about this show on Apple Podcasts - I haven’t had ANY new reviews there for quite a while, I could use one! That would be amazing if you could help me out! Thank you!

Thank you for listening to us and for joining us on yet another adventure in Theater History, Philadelphia.