The "Little Theater Movement" arrives in Philadelphia, bringing modern plays and creating new venues - including the Walnut Street Theatre.

The "Little Theater Movement" arrives in Philadelphia, bringing modern plays and surprising new venues - including the Walnut Street Theatre, where The Green Goddess was given a World Premiere tryout run in December of 1920.

For a blog post with images of the stories and topics we discuss in this episode, go to our website: https://www.aithpodcast.com/blog/green-goddess-dressing-notes-to-episode-66/

If you liked the show, leave a Review on Apple Podcasts! https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/adventures-in-theater-history-philadelphia/id1562046673

Follow us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AITHpodcast

Follow us on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aithpodcast/

Mastodon: https://historians.social/@schmeterpitz

Our website: https://www.aithpodcast.com/

To become a supporter the show, go to: AITHpodcast@patreon.com

© Podcast text copyright, Peter Schmitz. All rights reserved.

℗ All voice recordings copyright Peter Schmitz.

℗ All original music and compositions within the episodes copyright Christopher Mark Colucci. Used by permission.

© Podcast text copyright Peter Schmitz. All rights reserved.

© Podcast text copyright - Peter Schmitz. All rights reserved.

[AITH OPENING MUSIC]

Welcome back to Adventures in Theater History! Here on this show we bring you the best stories from the deep and fascinating history of theater in the city of Philadelphia. I’m your host Peter Schmitz. Our original theme music is by Christopher Mark Colucci. Come along with us as we really begin to tell the story of Philadelphia, The Tryout Town.

[TRYOUT TOWN THEME MUSIC]

In this episode we return once again to the Walnut Street Theatre on the corner of 9th and Walnut - it’s a famous Philadelphia theatrical space that we’ve returned to again and again during our first two seasons.

But as the second decade of the 20th century arrived, the Walnut was struggling to keep its position as an attractive house for touring theatrical productions. It was still, after all a classic Victorian Era theater, with a proscenium stage that looked out into a house that had two encircling horseshoe balconies, each backed with dark solid walnut paneling, and with cast iron structural posts that naturally impeded some of the audience's view - and then a third level, the gallery, high above that, pressed almost against the ceiling. Now back in the 19th century, that had been normal, and no one minded. The Academy of Music, built in the same era, had these same posts - indeed you can still see them in the Academy there today. But by 1910 all newer Philadelphia theaters, like the Garrick and the Forrest and the Adelphi and Hammerstein’s Opera House all had wide open sweeping balconies and loges, with no obstructions. The Walnut was already in a rather unfashionable part of town, and it was starting to lose its appeal as a touring venue, especially after city authorities restricted its seating capacity due to changes in modern fire safety regulations. The backstage dressing rooms were cramped, old and musty. The Theatrical Syndicate stopped sending prime touring shows to the Walnut - it was getting only second rate tours of plays and musicals that had long since lost their appeal on Broadway - and well, just about everywhere else, too.

Then - to top this all off - in April 1912, Henry B. Harris, the theatrical manager who at that point held the lease on the Walnut, died in the sinking of the Titanic. There was a huge resulting legal struggle over his estate, and the lease changed hands several times in the aftermath, including for a brief period to Louis B. Mayer, the future movie mogul, and for another period to Leon Leopold, the brother of the Philadelphia vaudeville comedian Ed Wynn. But everyone who ran the venue struggled with the fact that the old building was just not up to code. Maybe it would have to be torn down, as the Chestnut Street Theatre, another nearby huge old Victorian style house, was in 1917.

But we’ve been talking about the lease. Who owned the Walnut? Would they not pay to upgrade it and save this iconic Philadelphia institution? Well you probably don’t remember, but I’m here to remind you, how the great American actor Edwin Booth had bought the Walnut, back in the 1860s, along with his brother-in-law the comedian John Sleeper Clark. Well, as it happened, Sleeper Clark and Booth had a terrible falling out, right after Edwin’s brother John Wilkes assassinated President Lincoln. To settle the dispute, Booth signed control of the Walnut over to Sleeper-Clark. Sleeper-Clark had left the US, but he had retained ownership, and the title had stayed with his descendants, after he died in 1899. The family were happy to hold onto it as a source of small but steady rental income - but they weren’t really public-spirited custodians of theater history.

After the First World War ended in 1918, the Walnut was still limping along, partly a touring house, partly a vaudeville venue, sometimes showing films. A millionaire coal mining heir from West Virginia who had gotten into producing plays named James P. Beury had taken over the lease. Then in the fall of 1919, the Great and Glorious Strike by the newly-formed Actors Equity Association in New York forced theatrical producers to make significant labor concessions - including paying actors for rehearsals (which amazingly, was usually not done back then) and improved rights for touring companies. I’m pleased to report that our old friend Ethel Barrymore was a true inspirational leader in the union’s victory, as the Queen of Broadway her open support meant that the Big Stars were showing solidarity with all the character actors and chorus dancers. Also leading the charge was another familiar figure, Ed Wynn, a big star in Shubert musicals, who had proved to be a master strategist at winning concessions from his bosses. However, the provisions of the new production contract that finally settled the strike that meant the economics of the Walnut’s smaller potential box office returns just didn’t work anymore. The Clark family looked to sell the Walnut - to Beury, or to anybody really, even if that meant it would be torn down - and a century’s worth of the city’s theatrical history would vanish with it.

[TRANSITION MUSIC - Gounod - Funeral March of a Marionette]

But what if the Walnut didn’t have to be a Big Theater anymore - what if it could be . . . A Little Theater?

And by little theater, I don’t mean it would become a tiny basement venue or a toy theater. “Little Theater” was a term of the early 20th century that described what was also called the Art Theatre movement - creating plays and productions for purely Art’s sake, rather than crass commercial success. It was a vision of the theater as temple of Deep Truth and Profound Beauty, in an era when vaudeville acts and movie melodramas and the girl-packed Broadway revue “leg shows” were becoming more and more prevalent in popular culture.

In the United States, the Little Theatre Movement was a result of young American playwrights, directors, dramaturgs, stage technicians, stage designers, and actors, who were all influenced by new trends European Theater - such as the ideas of Max Reinhardt, who founded the small Schall und Rauch ("smoke and mirrors") Kabarett in Berlin to perform satirical plays and edgy Symbolist dreamscapes. Also influential were the plays of Maurice Maeterlinck in Belgium, the innovative black box theater designs of Adolphe Appia in Switzerland, the experimental concepts of Gordon Craig, and the staging methods of Andre Antoine at the Théâtre Libre in Paris, of Otto Brahm at the Freie Bühne in Berlin, of Strindberg at The Intima Theater in Stockholm and Stanislavsky at the Moscow Art Theater in Russia.

The type of plays that were performed in Little Theaters often explored much more serious topics of sexual frankness, social consciousness and psychological depth that would be allowed in most commercial and state-run theaters. In London, the critic William Archer used his knowledge of Norwegian to take it upon himself to translate the dramatic works of Henrik Ibsen into English for the first time, for example. But because the official censorship of the Lord Chamberlain’s office would never allow plays like Ghosts or Hedda Gabler to be actually performed on London’s public commercial stages, Archer, together with the American actress Elizabeth Robins, helped to mount Ibsen’s plays in small ‘private clubs’ - in which theatergoers bought memberships, you see, not tickets - to get around these strictures. Using a similar arrangement, later William Archer helped to found the small The Century Theatre in London, which staged such plays as George Bernard Shaw’s Mrs. Warren’s Profession, which frankly examined such topics as prostitution and women’s role in modern society, and Henry Granville Barker’s Waste, which advocated for the disestablishment of the Church of England and the legalization of abortion.

Now, in most college theater history courses, including mine, at this point we would likely discuss the American little theater movement, and talk about The Provincetown Players, who produced Eugene O'Neill's first one-acts, the Washington Square Players, the Neighborhood Playhouse, the Pasadena Playhouse, and so on. But because we are discussing Philadelphia theater, we’re going right to its own iconic The Little Theater on Delancey Street, in the middle of the wealthy Rittenhouse Square neighborhood to the west of Broad Street - it still stands and thrives today, and is more familiar to most Philadelphians as “Plays and Players.”

It began as a social club. Founded by a group of wealthy and well-connected Philadelphians who were eager to foster non-commercial theater, early supporters included the actress Maud Durbin Skinner, Beulah Jay, Edward Jay, and F.H. Shelton. Their stated objective was to produce a "theater of ideas." And many of these initial ideas were about sexual freedom and political enfranchisement for American women. The building itself, intended for use as a school for drama as well as a performance space, was designed by eminent architect Amos W. Barnes. The auditorium held less than 300 people. But it was elegantly and eruditely decorated.

On March 3, 1913, Philadelphia's Little Theatre was finally ready for its grand opening, and the group of founders staged its first play: The Adventures of Chlora. The play had been in rehearsal for many weeks, and its opening had been delayed several times by last-minute construction difficulties. On the evening of March 3rd, the audience included Dr. S. Weir Mitchell and his family, as well as Mr. and Mrs. Thomas Shelton. During intermission, all members of the audience were invited to view the lower level lounge, which was furnished with old prints and decorated "in mission style." Punch was served to the audience by members of the Little Theatre Club.

The Adventures of Chlora was billed as "an Austrian comedy." It had no author listed, but was likely written by one of the Little Theater's membership. The play was undoubtedly inspired by the infamous 1897 drama La Ronde by Arthur Schnitzler, which detailed a series of sexual encounters.

"Briefly, the story is formed by a series of five love ventures of an attractive and witty young maid who bears the title name, " wrote a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer. "Mrs. B.E. Jay, the director of The Little Theatre, has selected a number of well-known and experienced artists headed by Oza Waldrop, a clever comedienne recently featured in Speed, to form the cast. The other members of the company are Hilda Englund, a distinguished Swedish actress; [and] Mabel Wright, who was seen with Dustin Farnum in The Virginian."

According to a reviewer, the performance went well, on the whole, but he cautioned that "the acting organization has not found its level yet." The plot centered around "Chlora, an oversexed girl, with a longing for 'strong and adventurous' male companions, [who] resolves to experience the delights of a chain of flirtations. Her victims are an aviator, who falls through the skylight into her boudoir; a military officer, whom she encounters in a ruined abbey; a Viennese bachelor, a wealthy man, and a summer man, so called. All yield to her frank advances, and the verbal sparring between the men and the woman is spun out to a climax in each one of the episodes." The scenes evinced considerable laughter from the audience, though the critic thought the dialogue, on the whole, was quite undistinguished. Whoever wrote the play, said the critic, they were certainly not Austrian.

The Little Theatre kept going throughout the 19-teens, mostly powered by its wealthy, enthusiastic and socially prominent backers. We are going to come back to this jewel box of a theatrical space in a later episode, so I rather reluctantly lay the topic aside for the moment. But suffice it to say that although the plays produced there were often quite politically controversial, on the whole the ethos of the Little Theater movement was gaining a great cachet amongst the Philadelphia elite.

These included Charles Cook Wanamaker and James P. Beury. Those are two famous Philly names, and indeed if you know Philadelphia and your ears perked up, well yes those Wanamakers. True, Charles C. Wanamaker was only the nephew of the great John Wanamaker, the famous department store owner and philanthropist. Charles had worked for many years as the City Editor of the Philadelphia Ledger, but in middle age he seems to have had some sort of career crisis, because he gave it up to become the manager of the Garrick Theatre - a prestige theater, even though it hosted commercial productions. In the upper social circles he traveled in he was a great advocate for improving and supporting a better kind American theater in Philadelphia, and in this cause he managed to recruit a Very Wealthy friend of his to move his family to the city, the lessee of the Walnut Street Theatre, James P. Beury.

If that family name seems familiar to you, it may be because his brother was Charles Beury, the banker and President of Temple University. (It’s spelled B-E-U-R-Y, by the way, but always pronounced ‘berry’ like the fruit - although of course in a Philadelphia accent it comes out “Burry”) The famously long-vacant and graffiti-emblazoned “Beury Building” aka the “Boner 4Ever” building on North Broad Street is named after him. But again, we’re talking about his brother, James Beury, the guy who had been leasing the Walnut. And James Beury bought the building outright from the Sleeper-Clark heirs in the Spring of 1920. And then Beury immediately announced: he was going to tear it down and build a larger version of the Little Theater near Rittenhouse, where he could properly produce the great new American drama of the 20th Century. Charles Wanamaker would be his business manager.

[TRANSITION MUSIC ]

The last play performed in the old house was a musical romantic comedy, Down Limerick Way, in which the Irish tenor Fiske O’Hara had ample opportunity to sing about his love for his girl, and for the Ould Sod of the Emerald Isle. And that was it. After 112 seasons, the venerable Walnut, “The Oldest Theater in America,” had come to the end of its run.

But here I’m presenting an obvious and unsubtle misdirection - a pointedly false ending, right? Like when the main character dies in a TV show that’s literally named after him? Because we know the Walnut Street Theatre stands today, I walked you all through it in an episode just last Spring. Well there was a reason I called that episode “the WALLS of the Walnut Street Theatre.” Because the walls are what saved the place, or at least some of it.

James Beury was informed by the City of Philadelphia that its zoning code would require that he set back any totally new building ten feet from the old property line. And he didn’t want a little Little Theater, he wanted a big Little Theater - even bigger than the 600-seat Little Theatre then being renovated and improved on 44th Street in New York. (You may now know it by its present name, The Helen Hayes Theatre.) Beury was working in concert with the Shubert Brothers organization, and they had promised to send prime quality tryout productions his way if he had at least 1800 seats. So together with his architect Charles H. Lee, he decided to rebuild the theater within the confines of the old one, keeping the exterior walls, some of the old rafters, and most of the proscenium wall - the one that Pepin and Breshcard had erected when they expanded their circus in 1812 - dividing the audience from the stage - but bearing the evidence of the old stable doors for their horses.

But everything else had to go - and the demolition teams immediately went to work. First they cleared out all the old property rooms (Goodbye to a stage diary which had belonged to Junius Brutus Booth, goodbye to all the old furniture from the days of Edwin Forrest, goodbye to the skull of Pop Reed!). Then went the old costume collection which had Shakespearian clothes made for Edwin Booth. Historic stage machinery, like a windlass which had been used to haul up the stage curtain, made of the solid trunk of a tree, was hauled out. The old cigar store which had occupied the street corner for decades was torn out to create a new box office. The words “Oldest in America” and the date of its founding “1808” were removed from the facade. Beury wanted to emphasize the modernity of his theater from now on, not remind everyone of its past.

And then the workers turned to the interior of the building. The audience areas and the lobbies were completely ripped down, as old cast iron fixtures and solid walnut paneling were removed. The backstage dressing area and green rooms, which had incorporated the rooms of an old Philadelphia house which had once stood there, were dismantled. Old desks and mirrors from offices and dressing rooms were auctioned off, and some material, like piles of old theater programs and playbills, were sent to the Pennsylvania Historical Society or the Charlotte Cushman Club. But much was just quickly tossed into the dumpster. Beury and Wanamaker did send a lot of the old wood paneling off to become commemorative canes and walking sticks, which he distributed to his friends and financial supporters. But everything else went to some landfill. Everything, except for the old carved wooden eagle grasping a shield that had always flown at the pinnacle of the Walnut’s proscenium arch - it was once called the American Theatre, after all. The eagle was given a new coat of gold paint and was re-installed in what was now a mostly Georgian-style interior, with white paneling everywhere and wine-red upholstery on the seats. In the center of the ceiling was a crystal chandelier, saved from the ballroom of another Philadelphia landmark, the Bingham House hotel at 11th and Market, which had also just been demolished that same year.

And that is why when people confidently tell me that they already know the Walnut is the oldest historic theater in Philadelphia, which is certainly its reputation, I think about this 1920 disembowelment (and indeed the subsequent 1970 total reconstruction which tried to reverse some of its effects), and I always think: well, bits of it. It’s a little like the famous paradox of Theseus' ship - as it is rebuilt piece by piece over the years, at what point is the name all that truly remains?

But you know I can’t find much evidence of people back in 1920 being too sad about the hollowing out of the Old Walnut. After the end of the Great War, it was a New Age, people wanted New Things - the 19th Century society and politics and its style of theater was old and discredited and fussy. People wanted clear sight lines, comfortable seats, working plumbing, air conditioning and proper ventilation. A single sweeping open balcony and expansive lounges and lobbies. It was a proper place to exhibit works of the New Modern American Theater. And I suppose actors certainly appreciated the new plumbing with modern bathrooms and showers in the dressing rooms constructed behind the stage area, and the modern green room. The work took eight months to complete, and the newly renovated and updated Walnut Street Theatre was scheduled to reopen the week after Christmas. December 27th, 1920.

And what was selected to be the first show to mark this new dawn of Modern Theater in The Quaker City? Well appropriately for our Season Three, it was a World Premiere, a play that was trying out in Philadelphia for three weeks before moving on to its Broadway premiere in New York. And, what had Mr. Beury and Mr. Wanamaker (and their silent partners, the Shuberts) chosen to inaugurate what the programs (handed out that evening to the audience) called “the Newest Oldest Theatre in America”? A classic work of American dramatic literature? A Shakespeare play? A new work by an exciting young American playwright like Eugene O’Neill? An exciting new musical by the young composer Irving Berlin or George Gershwin? Nope, none of those things.

Fittingly, perhaps, for a city whose theaters had always historically been highly influenced by English prototypes, the first play at the New Walnut was by the great eminence of the progressive the London stage - the translator and critic William Archer, the great friend of George Bernard Shaw, who had introduced Ibsen to the English speaking world! But this was Archer’s own work, which he had dedicated himself to ever since learning that his only son had been the first real play he had ever written himself: The Green Goddess.

[TRANSITION MUSIC ]

So, what was Archer’s The Green Goddess? Was it a serious play set in a tightly constructed plot like Ibsen’s famous A Doll’s House? Or was it a more symbolic and mystical work, like Stridberg’s later works - perhaps a mourning for his lost son and millions of other needlessly slaughtered young men during the Great War? Was it a witty examination of social issues set in the midst of witty and stunning dialogue, like those of George Bernard Shaw? Or, since Archer had recently published a long deeply researched sociological book about race relations in the United States, entitled Through Afro-America - was it an impassioned plea for deeper historical understanding of the plight of the long-oppressed? Or since Archer had actually attended shows at the old Walnut, when he had toured America in earlier years, was it a meditation on the changing nature of theatrical tastes?

No, it was none of those things either! It was a literal potboiler - a play that Archer hoped would be a huge commercial success and help to fund his retirement and old age. Directed by Winthrop Ames, it was an attempt at a thrilling melodrama, with an Exotic Setting: the fictional small Asian principality named Rukh, somewhere vaguely around Afghanistan or Nepal. Archer had spent the war years working for British Imperial War Propaganda Bureau, and he had evidently deeply imbibed the current obsessions of bureaucrats and diplomats who were trying to shore up and re-launch another tottering Victorian institution: the British Empire and the British Raj in India! Indeed, if you want to know more about the worldview that Archer’s play was inhabiting, I can recommend nothing more than episodes 88 and 89 of that excellent history podcast called Empire created by William Darymple and Anita Anand, which will fill you in on the exact mindset of the last stages of “The Great Game,” as Britain and Russia struggled to keep each other at bay in Central Asia - but we’ll leave that aside for our purposes.

Here’s Archer’s stage directions about the opening setting he desired: [MUSIC UNDER, ]

The curtain rises on “a region of gaunt and almost treeless mountains . . .Clinging to the mountain wall in the background, at an apparent distance of about a mile, is a vast barbaric palace, with long stretches of unbroken masonry, crowned by arcades and turrets. The foreground consists of a small level space between two masses of rock. In the rock on the right a cave has been roughly hewn. Two thick and roughly carved pillars divide it into three sections. Between the pillars in the middle section can be seen the seated figure of a six-armed Goddess, of forbidding aspect, colored dark green . . . Projecting over the rock mass on the left . . can be seen the wing of an aeroplane. . It has evidently just made a rather disastrous forced landing.”

“The pilot and the two passengers are in the act of extricating themselves from the wreck and clambering down the cliff. The pilot is Dr. Basil Traherne; the passengers are Major Anthony Crespin and his wife Lucilla. Traherne is a well-set-up man, vigorous and in good training. Crespin, somewhat heavy and dissipated-looking, is in khaki. Lucilla is a tall, slight, athletic woman, wearing a tailor made tweed suit. All three wear aviation helmets and leather coats. Their proceedings are watched with wonder and fear by a group of dark and rudely clad natives, rather Mongolian in feature The natives chatter eagerly among themselves. A man of higher stature and more Aryan type, the priest of the temple, seems to have some authority over them.”

So already, we’re in wild and wooly dramatic territory, and all our modern warning signals are going off with words such as “rudely-clad natives rather Mongolian in feature” and “Aryan type”. But it gets even more bonkers, when the natives take the three stranded Brits to their leader, the Rajah of Rukh. The Raja, as it turns out, is a tall gaunt man wearing an elegant turban - who has been educated in the West, and so has impeccable English and complete knowledge of the affairs of his new guests. He plays them his phonograph records, he’s particularly fond of Gounod’s “Funeral March of a Marionette” He is the ultimate authority over the acolytes of the Green Goddess, and also willing to accept help from the Russians as they strove to maintain influence in that part of the world. Though they are deep in Himalayan isolation, it seems he has access to a huge secret radio transmitter that he uses to keep in touch with the outside world. The Raja immediately begins to plot how to use the stranded English trio for his own political ends - principally the exchange of his prisoners in return for his half-brothers who are about to be executed for anti-British terrorism by the colonial government - and if that gambit does not succeed, that they must all be ceremonially executed in revenge, and to assuage the Green Goddess.

So, as I said, quite a melodrama. When Major Crespin asks the Raga if he could possibly let them go, for his wife and children’s sake, or for a ransom payment - the Raja angrily replies:

You don’t know how my faithful subjects are looking forward to tomorrow’s [execution] ceremony. If I tried to cancel it there would be a revolution. You must be reasonable, my dear sir. . . .What can you promise that is worth a farthing to me? No, Asia has a long score to settle against you swaggering, blustering, whey-faced lords of creation, and by the gods, I mean to see some of it paid tomorrow!

Although of course, we do learn there is a further inducement to offer him, because the Raja also wants to take possession of the beautiful Englishwoman, whom he lusts after. She scorns him - for the moment, but this further peril only adds fuel to the melodramatic suspense! [MUSIC OUT]

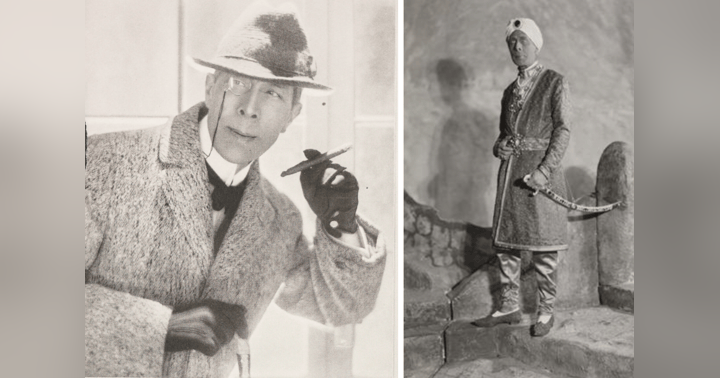

The role of the Raja of Rukh was played by a slender and long-faced actor named George Arliss. George Arliss was yet another of those British actors who had come to America as a young man and had stayed to become a star. For the past twenty years he had been a fixture of the Broadway stage, known most especially for his work in a play about the Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. At first Archer had despaired of ever finding the right actor for the Raja, since Sir Henry Irving was long dead, [MUSIC, UNDER] but Arliss had slid right into the role, inhabiting it with skill and gleefully creating a character of wicked charm and insidious guile. And of course he was in what we would now call brownface makeup, as were all other actors onstage who were playing his subjects - all fanatical devotees of the local deity, the Green Goddess. There were only two other white characters in the play: Watkins, the treacherous Cockney aide to the Raja, who eventually gets heaved out of a palace window as the three captives take control of the palace radio to call for help and try to make their escape, and a British military pilot who comes in at the end - after having bombed Rukh and all its people into submission. By that point Major Crespin has already been shot and killed by the Raja, which allows Lucilla and Traherne to finally admit their love for each other.

The Raja, having been defeated in the end, is philosophical, as Traherne and Lucilla depart, remarking that he’ll probably have to abdicate his throne now, but that he’ll likely see them again on the Riviera some day. As for losing the white woman of his deepest desires? “Well - Well,” he says to himself, coolly lighting a cigarette on a flame from a temple brazier, “she’d probably have been a damned nuisance.” [UNDERSCORING OUT]

Well this sort of melodrama was just the sort of thing that American audiences adored back then. Lots of gripping action, lots of exoticism, lots of special effects, lots of sex in the air - especially the prospect of sexual bondage to a foreign exotic villain. Melodramas of that sort were just going to be Broadway’s bread and butter for the next decade - one of the most commercially successful decades ever in the history of the American theater. I just didn’t see it being kicked off by a guy who had literally made his reputation promoting Shaw and Ibsen. But it all kicked off splendidly that night at the corner of 9th and Walnut. Indeed, the Philadelphia theater critics all raved about The Green Goddess in their papers the next day, and Philly audiences flocked to see it. The three-week run at the new Walnut was completely sold out. Archer wrote happily back home to George Bernard Shaw that now he was a successful playwright, too, the total box office receipts had been almost $20,000! To his brother Wiliam he confided his fears that this tryout town success was all rather surprising beyond his wildest dreams, but “I hope it hasn’t gone up like a rocket in Philadelphia, to come down like a stick in New York.”

But it didn't. The play went on to run for the rest of the season at the Booth Theatre on Broadway - and then Arliss toured the country with it for the next year. While he was in San Francisco with it, a chef at the hotel named a new salad dressing for the play in his honor - so if you’ve ever had green goddess dressing, you can thank Arliss and Archer and even the Walnut Street Theatre, in a way. The property then was snapped up by Hollywood, and Arliss repeated the role of the Raja of Rukh in a silent version in 1923 - which is easily available on YouTube, and then he played the role again in an early “talkie” in 1930 - it still occasionally shows up on old movie channels on TV, you might want to catch it sometime.

Anyway, to my mind the success of The Green Goddess and the apparent appeal of the Newest Oldest Biggest Little Theater in America really starts the Tryout Town Era in Philadelphia. The Shuberts, in particular, who will be the focus of our next episode, had certainly noticed how useful Philly could be for their purposes. From then on they made sure that not only musicals and revues and operettas would regularly come through the Quaker City on pre-Broadway tryout tours, but so would serious plays, light comedies and many many melodramas, all hoping to replicate the success of Archer’s play - which did earn him enough to support him in his old age - or rather it would have, if he hadn't suddenly died on December 27, 1924, exactly four years to the day after the world premiere in Philadelphia.

For the new owner and manager of the Walnut, certainly, the future seemed bright. In “The Call Boy’s Chat” column of the Inquirer in early January of 1921, a reporter wrote that “there is every evidence of a modern playhouse, with the elegance and comfort one naturally expects in these days of progress and new-fangled ideas.”

“I have been assured,” The Call Boy continued, “by both Mr. Wanamaker and Mr. Beury that the attractions for the season will measure up to the standard set by Mr. Arliss, which argues well for the patrons of the house.”

However, he concluded, he was still a bit miffed because of the removal of the date “1808” on the exterior of the building. He had always liked that - but he consoled himself with the thought that maybe it would be put back up - some day.

[MUSIC UNDER - Gounod, again] That’s our show for today. The Sound editing and engineering was all done by My Humble Self, here at our studios in our World Headquarters high atop the Tower of Theater History. If you’ve been enjoying this season of the podcast, or have any thoughts or suggestions, drop us an email at AITHpodcast@gmail dot com. We would love to hear from you! To support our show and get access to bonus material and special insider info about Philly theater history, our Patreon page is Patreon dot com/AITHpodcast. Or, another way to thank us, is to leave some stars and/or a review about the show on Apple Podcasts or Spotify - or you can do that right on our website, AITHpodcast.com that helps us out so much. And while you’re visiting the website check out the blog post for this episode - we'll share some images of The Green Goddess and the Walnut and many of the events and performers that we talked about today. [MUSIC OUT]

Thank you for listening, and for coming along on another Adventure in Theatre History, Philadelphia.

[AITH END THEME]

© Podcast text copyright - Peter Schmitz. All rights reserved.